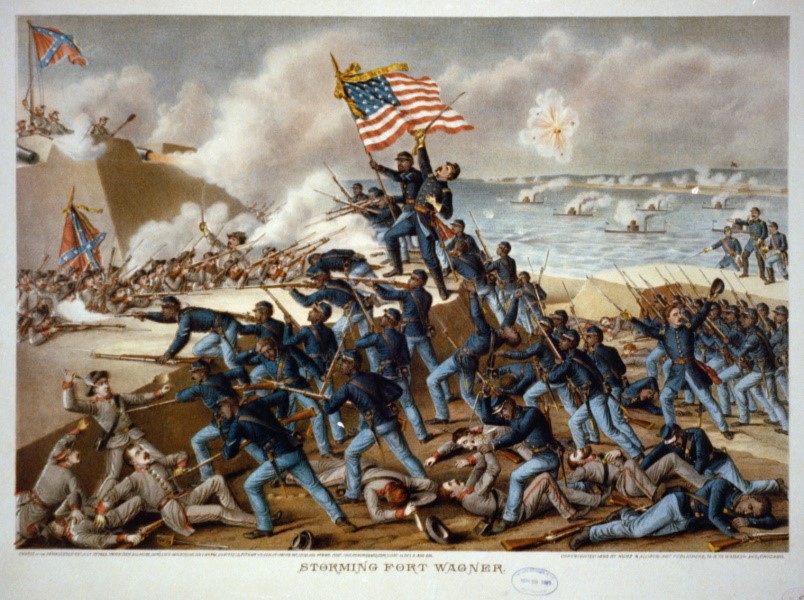

This 1890 print by Kurz and Allison captures the moment of Col. Shaw’s death during the assault on Fort Wagner. (Library of Congress)

On July 18, 1863, a large force of Union Soldiers advanced in formation toward Confederate fortifications outside Charleston, South Carolina. As the sun set, Confederate defenders opened fire on the 5,000-strong assault force. Despite sustaining heavy casualties, the regiment pressed forward, scaling the fort’s parapet and engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Col. Robert Gould Shaw, the regiment’s commanding officer, led his men with the cry “Forward, 54th!” before being mortally wounded by enemy fire.

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, formed on March 13, 1863, was a unit of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and served in the American Civil War. Although their assault on Fort Wagner ultimately failed, the bravery of the 54th made them famous across the country, demonstrating that Black Soldiers could fight as effectively as their white counterparts.

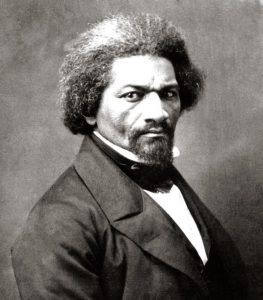

African Americans had served in the Army and Navy since the early years of the United States, but few remained by the time of the Civil War. When the war began in April 1861, many abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, believed that free and formerly enslaved Black men should be allowed to join the Army. Douglass, a former enslaved person and one of the most influential abolitionists in the North, famously declared, “…who would be free, themselves must strike the blow.” However, many in the North were hesitant to allow African Americans to fight for the Union.

Frederick Douglass, who recruited for the USCTs, saw two of his sons, Lewis and Charles, serve in the 54th. His famous quote, “Who would be free, themselves must strike the blow,” was inspired by his own experience of resisting a whipping at age 16, a moment he considered the turning point of his life. (New York Historical Society)

By 1862, President Abraham Lincoln had come to believe that slavery should be abolished and that African Americans should have the opportunity to fight for their freedom. Following the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which granted freedom to all enslaved people in Confederate-held territory. The proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, also opened the door for African Americans to serve in the Union Army.

On January 26, 1863, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew to raise African American regiments. Andrew, an abolitionist, enlisted the help of other Northern abolitionists, including Douglass, to recruit men for the regiments. Although the enlisted men were Black, the Army required that officers be white. Andrew selected Col. Robert Gould Shaw, the son of a prominent abolitionist family, to lead the 54th Massachusetts, with Maj. Edward Needles Hallowell as the regiment’s second in command. Recruitment for the regiment was so successful that a second unit, the 55th Massachusetts, was formed to accommodate the excess recruits. After months of training, the 54th was mustered into federal service on May 13, 1863, and deployed to Union-occupied Beaufort, South Carolina, where they joined another USCT regiment, the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers. Together, the two units conducted a raid on Darien, Georgia. Shaw criticized the use of his men for pillaging rather than combat, but soon they would have their chance to prove themselves in battle.

This photograph of Col. Shaw was taken during his recruitment efforts for the 54th. (Library of Congress)

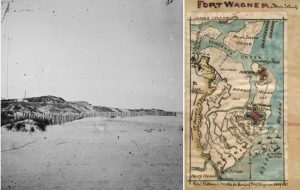

One of the Union’s main objectives in South Carolina was the Confederate port city of Charleston. The Union’s Civil War strategy included a blockade of the Confederate coast, known as the Anaconda Plan, which required the capture of several Confederate coastal forts, including those defending Charleston. To blockade and capture Charleston, Union forces needed to seize the heavily fortified Fort Wagner.

A contemporary mural from the George F. Landegger collection depicts Shaw’s death during the assault on Fort Wagner. (Library of Congress)

After the failed assault on Fort Wagner, the 54th spent several months recovering. Under the command of Hallowell, now a colonel, they continued to serve in the South, participating in battles such as the Battle of Olustee in Florida, the largest battle of the war in that state. Despite their valor, the men of the 54th faced discrimination, including unequal pay compared to white Soldiers. After persistent efforts by Hallowell, Congress passed a bill on September 28, 1864, securing equal pay for all USCTs.

The men of the 54th Massachusetts served with courage and honor throughout the Civil War. Approximately ten percent of all Union Soldiers were USCTs, and over 36,000 of them died during the war. Their service paved the way for future African American Soldiers, including the Buffalo Soldiers. However, recognition from the United States was slow in coming. Sgt. Carney, despite his heroic actions at Fort Wagner, did not receive the Medal of Honor until May 23, 1900, 37 years after the battle. The bravery and contributions of the 54th and other African American Soldiers were a crucial part of the Union’s victory in the Civil War.

This image of Sgt. Carney bearing the 54th’s colors was taken in 1864. National Museum of African American History and Culture

Although they sustained heavy losses, the 54th pinned down the defenders, allowing other regiments to advance on Fort Wagner. They managed to enter the fort, though a Confederate counter-attack pushed out the remaining Union Soldiers. The attack on Fort Wagner failed, with the Union suffering horrific losses. 1,515 Soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured. The Confederates lost only 174 men. Confederate brigadier general William B. Taliaferro, commander of the defenders, wrote, “In front of the fort the scene of carnage is indescribable… I have never seen so many dead in the same space.” The 54th Massachusetts sustained the worst losses; almost half of the 600 men were killed, wounded, or captured, including Shaw. The Confederates buried Shaw in a mass grave with his men. They viewed this as the ultimate insult for a white man to be buried with African Americans. Shaw’s family felt differently; they believed it an honor that Shaw was buried in the field with his Soldiers.

This contemporary mural from the George F. Landegger collection dramatizes Shaw’s death during the assault on Fort Wagner. Library of Congress

The 54th spent several months recovering after the Fort Wagner debacle. Under the command of Hallowell, now a colonel, the 54th spent the rest of the war attached to various Union elements in the South. After Federal forces finally captured Fort Wagner on Sept. 6, 1863, Brig. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore ordered an expedition to Florida to disrupt enemy operations. The 54th participated in this expedition and fought in the Battle of Olustee, the largest battle of the war to occur in Florida. After Confederate forces pushed back the main Union line, the 54th fought a successful rear-guard action which allowed the attacking force to retreat.

The 54th continued to operate in South Carolina, participating in the Battle of Honey Hill and the Battle of Boykin’s Mill. Yet, despite their valor and service, many refused to treat the men of the 54th equally. For the same service, the Army paid them less than their white counterparts and often overlooked them when awarding the Medal of Honor. After persistent efforts by Hallowell, Congress passed a bill on Sept. 28, 1864, which secured equal pay for all USCTs.

The men of 54th Massachusetts served courageously and honorably. Around ten percent of all Union Soldiers were USCTs and over 36,000 of them died during the war. Their service opened a door for future African Americans to join the Army, including the formation of the Buffalo Soldiers, a group African American cavalryman. Yet, recognition from the United States eluded some USCTs, including Carney. Although he received an honorable discharge, the Army never recognized him for his actions at Fort Wagner. On May 23, 1900, 37 years after the battle at Fort Wagner, Carney finally received the Medal of Honor for his gallantry in rescuing the 54th’s colors. Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists were proven correct, the 54th and other African American Soldiers contributed to victory in the Civil War.

This small fragment is all that is known to remain of the 54th’s colors from the assault on Fort Wagner. It is currently on display at the National Museum of the United States Army. NMUSA